On the 18th of August 1993, an American cargo plane on approach to Guantanamo Bay suddenly rolled over and crashed to the ground, sending a huge fireball rising over the secretive naval base. Fire crews rushing to the scene found the DC-8 consumed in flames — except for the cockpit, in which all three crew members were miraculously found alive. Investigators seeking to understand the cause of the crash were eager to hear what they had to say. But it soon became clear that this was not a case of a sudden emergency leading to a loss of control — the crash was caused by pilot error. The survival of all three pilots gave a unique perspective on mistakes and misperceptions about which investigators usually only get to speculate. Reconciling the pilots’ testimony with the recorded flight data, the National Transportation Safety Board revealed a surprising sequence of events that began when a crew suffering from severe fatigue encountered an unusual procedure rooted in the special political status of Guantanamo Bay.

American International Airways was a brand name used by what is now Kalitta Air between 1985 and 2000. Founded by American racing driver Conrad “Connie” Kalitta in 1967, AIA/Kalitta Air specializes in both scheduled and chartered cargo flights as well as chartered passenger services. During the 1990s, AIA ran cargo for the US Department of Defense out of its base of operations in Ypsilanti, Michigan, including hundreds of supply runs during Operation Desert Storm.

Much of its fleet at the time consisted of antiquated four-engine Douglas DC-8s. It was one of these DC-8s that operated a series of cargo flights between the 16th and 18th of August 1993, under the command of Captain James Chapo. A highly experienced pilot with over 20,000 flight hours, Chapo had spent more time flying planes than some entire crews. Joining him on the 4-day scheduled trip sequence were First Officer Thomas Curran and Flight Engineer David Richmond, both of whom also had thousands of hours of experience.

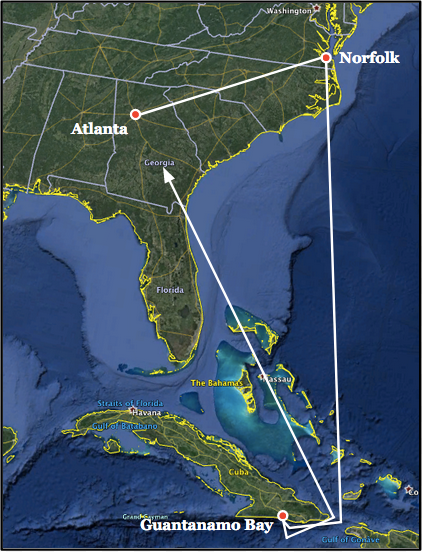

The pilots’ schedule first saw them complete an overnight flight from Ypsilanti to St. Louis, Missouri, then on to Dallas, Texas, where they arrived at noon on the 17th. The crew slept as best they could before reporting for duty again at 11:00 p.m. that night, at which point they continued on to Atlanta, Georgia, arriving just before 8:00 in the morning. Captain Chapo and First Officer Curran both lived in Atlanta and planned to go home to sleep and visit their families, while Flight Engineer Richmond checked into a hotel. But before any of them could get far, the company called them back. An AIA plane scheduled to pick up a load of submarine parts in Norfolk, Virginia couldn’t make it, and they needed someone else to take the flight. The shipment belonged to the Department of Defense and was bound for the US naval base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Flying to Norfolk, picking up the cargo, taking it down to Guantanamo, and returning to Atlanta would take at least eleven hours, and all of the pilots were reluctant to accept the assignment.

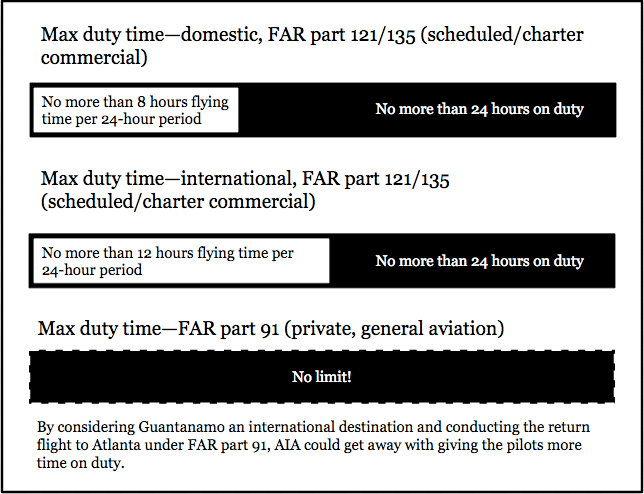

The pilots first debated whether the assignment was even legal. Eventually, they concluded that it was, but only due to a regulatory loophole. Because Guantanamo Bay was considered an international destination, they were allowed to be assigned up to 12 hours flying time within a 24-hour period on duty, rather than the 8 allowed for domestic flights. However, this was still insufficient to allow them to ferry the empty plane back to Atlanta at the end of the day. To get around this, AIA operated empty ferry flights under part 91 of the Federal Aviation Regulations, which applies to private, non-commercial flights and is subject to no duty time limits, allowing the pilots to legally exceed the maximum of 12 hours flying time. The pilots felt that this was pushing it, but while they could technically refuse the assignment, they all knew that if they turned it down, their superiors would want a good reason. Reluctantly, the crew got back on the DC-8 and headed to Norfolk.

“I was not particularly enthusiastic to go out for another 7, 8 hours of flying; I’d much rather have gone home and got a good night’s sleep…” — First Officer Thomas Curran

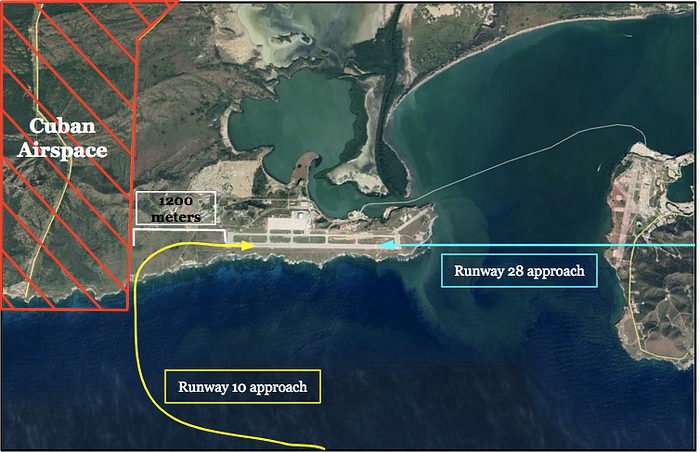

After picking up the cargo in Norfolk, the DC-8 took off for Guantanamo as AIA flight 808. The naval base at Guantanamo Bay predates the 1959 Cuban Revolution that brought a communist government to power on the island, and although the United States managed to keep the base after the revolution, it did not maintain any diplomatic relations with Cuba, resulting in a complex political situation. The land on which the base sits is a small piece of sovereign US soil, but it is surrounded on three sides by Cuban territory. American airplanes landing at Guantanamo Bay are not allowed to enter Cuban airspace. This creates a uniquely difficult situation for pilots landing at the base’s Leeward Point Field, and before flying there, all crews must watch an informational video depicting some of the hazards associated with the approaches to its two runways. The crew of AIA 808 had watched the video during training, but for Chapo and Richmond, this would be their first time actually flying to Guantanamo Bay. First Officer Curran had flown to Guantanamo years earlier when he was in the navy, but had never landed there in anything as large as a DC-8.

By 4:40 p.m., flight 808 had begun its descent into Guantanamo Bay, and the pilots had been on duty for 18 hours. All were getting tired. This fatigue manifested itself in a variety of ways, with Captain Chapo feeling increasingly lethargic and indifferent, while First Officer Curran felt exhilarated, perhaps even a little tipsy.

When suffering from fatigue, one of the first things to go is a person’s ability to make rational decisions and manage risk. This soon manifested itself in an alarming manner. Somehow, Captain Chapo got it into his head that it would be interesting to fly an approach to runway 10 instead of the default runway 28 (the same runway from the opposite end). Runway 28 involves a relatively straightforward approach from the east over the bay, while runway 10 is rarely used by large airliners due to its extremely difficult approach pattern. The threshold of runway 10 is only 1.2 kilometers from the Cuban border, meaning that American planes must approach it from the south over the sea, staying within the international boundary, followed by a sharp 90-degree right turn to line up with the runway at the last second. The timing of the turn must be impeccable. For obvious reasons, controllers rarely ask planes to use runway 10, and pilots rarely request it.

At 4:41, Captain Chapo said, “Ought to make that a one zero approach, just for the heck of it, to see how it is. Why don’t we do that, let’s tell them we’ll take one zero; if we miss we’ll just come back around and land on two eight.” Neither of the other pilots raised any objection, and no one mentioned the difficulty inherent to the approach.

The controller cleared flight 808 to approach runway 10, although she was plainly mystified by the pilots’ decision. She asked if they were sure they didn’t want to use runway 28, and First Officer Curran reaffirmed their earlier request. On board the plane, the pilots hastily prepared for landing, neglecting to discuss how they might perform a missed approach if they were unable to line up with the runway. At 4:52, the controller provided the pilots with a standard statement of caution issued to all aircraft approaching runway 10. “Connie 808,” she said, using the flight’s callsign, “Cuban airspace begins three quarters of a mile west of the runway. You are required to remain within the airspace designated by a strobe light.”

A strobe light had been set up on a guard tower where the border meets the ocean in order to assist pilots in locating the boundary. However, the trainee controller on duty at the time was unaware that the strobe light wasn’t working. Now the pilots expected to see a strobe light that wasn’t there. And they were growing increasingly paranoid about straying over the boundary, because they had heard spurious rumors that Cuban border guards would shoot at aircraft that violated their airspace.

“I remember, as we were approaching the shoreline, we were intimidated by the fact that we were told that there might be guards at the fence perimeter with guns.” — First Officer Thomas Curran

“Everybody told us, they’ll shoot you down, they’ll shoot you down!” — Captain James Chapo

Flight 808 made its second to last turn, heading north perpendicular to the runway. Now the crew began to search for the strobe light so that they could find the border. Unable to locate it, Captain Chapo asked, “Where’s the strobe?”

Both Curran and Richmond spotted a flashing light that they thought might be the strobe. Because the strobe was not actually on at the time, it is believed that they were seeing sunlight reflecting off the tin roof of a shack several hundred meters inside US territory.

“Right over there,” said Richmond, pointing at the light.

“Where?”

“Right inside there, right inside there,” Curran said.

Richmond observed that they were dropping below the minimum airspeed for the approach. “You know, we’re not getting our airspeed back there,” he said.

With their airspeed below the minimum, the approach was unstabilized, meaning that they should have initiated a go around and landed on runway 28 instead. But Captain Chapo wasn’t listening. “Where’s the strobe?” he asked again.

“Right down there,” said Curran.

“I still don’t see it.”

“Fuck, we’re never going to make this,” Richmond muttered. Once again, the others ignored him.

“Right over here,” Curran said again, growing almost as frustrated as his captain.

“Where’s the strobe?” Chapo asked, sounding more and more like a broken record.

Now even Curran was beginning to have doubts about their ability to line up with the runway. Unable to definitively spot the Cuban border, they had made the turn onto the penultimate leg too soon, and they wouldn’t have enough room to turn onto final approach. “Do you think we’re going to make this?” Curran asked.

“Yeah, if I can catch the strobe light,” said Chapo, apparently unable to think about anything else.

Now Chapo began the final turn toward the runway, starting 610 meters south and 914 meters west of the threshold. Aligning with the runway from this position in a DC-8 was impossible, but Chapo tried anyway. He banked 30 degrees to the right, the maximum typically used in normal operations. It wasn’t enough, so he banked more.

As Chapo focused on making the turn, he let his speed drop even lower, now down to 136 knots (252km/h). “Watch the — keep your airspeed up,” said Richmond, but no one acknowledged him. And Chapo kept banking — to 40 degrees, then 45, then 50. Maintaining a bank angle this steep would have required a speed of at least 147 knots.

As bank angle increases, the vector of the lift produced by the wings becomes more and more offset from the vertical, reducing its effectiveness in countering the force of gravity. This causes the plane’s stall speed (the speed below which there will not be enough lift to stay in the air) to increase. As Chapo steepened the bank, the plane’s stall speed kept going up and its airspeed kept going down until finally they met in the middle.

“I should have turned it over to Tom, but I was already just sorta out of it…” — Captain James Chapo

As the bank angle approached 50 degrees, a stall warning suddenly activated, shaking the pilots’ control columns to warn them of the impending catastrophe.

“Stall warning!” Someone called out.

But Chapo just kept banking, moving toward 60 degrees as he desperately attempted to line up with the runway. “I got it,” he said.

“Stall warning!” said both Curran and Richmond, almost simultaneously.

“I got it, back off!” Chapo shouted.

Someone yelled, “Max power!”

Another person screamed, “There it goes, there it goes!”

Numerous witnesses caught sight of the plane, banked to almost 90 degrees, falling nose first out of the sky just short of the runway threshold. The DC-8 cleaved sideways into the ground, its right wingtip digging a deep furrow through the earth before the entire plane cartwheeled in a huge ball of fire. The cockpit broke off like a pencil tip and rolled across the ground as flames consumed the fuselage.

“I don’t remember the exact moment of hitting the ground…” — Captain James Chapo

“My memory of the actual accident itself is gone.” — First Officer Thomas Curran

A group of firefighters conducting a training exercise witnessed the crash and immediately rushed to the scene to search for survivors. Burning debris lay scattered over a huge area, and the spilled fuel had started a grass fire that quickly began to burn out of control. As they arrived on the scene, the firefighters realized that the remains of the cockpit had come to rest away from the flames, and someone inside was calling out for help! Climbing in through a hole in the floor, they discovered all three pilots hanging sideways inside the mangled cockpit, seriously injured but alive. One by one, they extracted James Chapo, Thomas Curran, and David Richmond from the remains of the plane, all the while fending off the fire that had spread to several acres of grassland. The successful rescue came at the cost of their fire truck, which was burned over while its crew attended to the injured pilots.

In a rare moment of diplomacy between the US and Cuba, American officials managed to secure permission for an air ambulance to cross Cuban airspace in order to rush the pilots to hospital in Florida. At the same time, the National Transportation Safety Board assembled a team to go to Guantanamo Bay to determine the cause of the crash. They brought the black boxes back to Washington D.C., where investigators listened to the cockpit voice recording for the first time. They were astonished to hear Captain Chapo choosing to approach runway 10 “just for the heck of it,” a level of unprofessionalism totally unbecoming of his more than 20 years of flying experience.

The significance of the choice to land on runway 10 cannot be overstated. The NTSB reviewed the procedures for landing on runway 10 and concluded that the average DC-8 pilot wouldn’t be able to complete the approach without either exceeding bank angle limits or violating Cuban airspace. So why did Chapo take such a risk, and why did none of the other crew members object? Furthermore, why didn’t he go around when it became clear he couldn’t line up with the runway, and why did no one else take control?

The crew’s ability to judge the risks of the runway 10 approach was hampered in part due to a lack of information. Most airlines operating into Guantanamo Bay carried a special manual describing procedures at Leeward Point Field due to its special status, but American International Airways did not. The DoD contract officer in Norfolk typically briefed crews on special approach procedures before they flew to Leeward Point Field, but he failed to give this briefing to the pilots of flight 808 because he mistakenly believed Captain Chapo had been there before. As a result, the only prior knowledge the crew would have had about the approach to runway 10 was from the video they watched during recurrent training more than five months earlier — a video which the NTSB felt did not adequately highlight the risks.

Investigators examined the pilots’ schedules and realized that they also must have been severely fatigued. Chapo had slept only 8 out of the last 48 hours before the crash, half the amount he normally received. In that same time frame, Curran had slept only 10 hours, which was not much better. And on top of all that, they had run night operations for the past two days, throwing off their sleep schedules. Research by NASA had shown that repeatedly failing to get enough sleep can cause a person to accrue a sleep debt, which has a compounding effect on fatigue. This fatigue in turn can cause significant reductions in a person’s ability to process information, make decisions, and handle multiple simultaneous tasks. It was clear to the NTSB that the series of bizarre errors by an otherwise excellent pilot could only have occurred due to fatigue, which made him feel sluggish and detached from reality. Unable to properly assess risk, he decided to land on runway 10 instead of runway 28. Then once the approach began, he became fixated on the search for the strobe light that marked the Cuban border, unaware that it was offline. First Officer Curran also became fixated on helping Chapo find the strobe, causing them both to tune out Flight Engineer Richmond’s repeated assertions that their speed was too low and that they weren’t going to make it. This fixation appeared a second time when Chapo attempted to make the final turn from a point too close to the runway. This time, he became so focused on completing the turn that he didn’t notice he was effectively rolling his plane right into the ground.

“It still gets to me, because it still boils down to the captain, you know, the captain made a mistake and that’s a hard thing to live with all the time…” — Captain James Chapo

Interviews with the pilots shed more light on how they were feeling. Chapo described himself as a “day person” who had trouble with night shifts and didn’t sleep well during the day. He had slept for maybe four hours during the layover in Dallas the previous day, and it was not high quality sleep. His memories of the accident flight were foggy — he vaguely recalled Curran saying that he had doubts about the approach, but he couldn’t remember any of the crewmembers’ comments about their airspeed being too low or that they “weren’t going to make it.” This confirmed the investigators’ suspicion that his fatigued brain had simply tuned them out. Reviewing the cockpit voice recording, Chapo expressed consternation with his own behavior. “It’s very frustrating and disconcerting at night to try to lay there and think of how this — you know — how you could be so lethargic when so many things were going on,” he said to the NTSB. First Officer Curran, on the other hand, didn’t remember feeling fatigued at the time. But after reviewing his performance on the recording, he said he thought he was probably more tired than he had initially believed.

Investigators also looked into American International Airways and discovered many problems with the airline on an operational level. AIA’s operations were spread out over several US locations as well as Saudi Arabia and South America. The FAA inspector assigned to oversee the airline complained that he wasn’t given the funding to travel to these locations to see for himself how things were going. Two weeks before the crash, the inspector had sent a memo to his superiors stating that he could not oversee all of AIA’s operations due to lack of funds. He also stated that AIA tended to go no further than the bare minimum required to comply with regulations, and that he often had to resort to “unorthodox” methods to get AIA to comply with his recommendations. Furthermore, the relationship between pilots and airline management was poor. Repeated cases of abuse and verbal intimidation had pushed pilots to discuss unionization during the months leading up to the accident. The FAA inspector corroborated the pilots’ complaints, testifying that AIA’s management was extremely profit-driven and that pilots had reported numerous flight duty time violations. This created a culture where pilots were expected to take what they were given without regard for fatigue. Captain Chapo stated that he had never heard of an AIA pilot refusing an assignment due to fatigue, and one pilot who had done so told the NTSB that he was afterwards subjected to intimidation by his superiors.

“If you had an objection to taking a trip, you could be in for a little bit of a conversation with the boss…” — First Officer Thomas Curran

Part of the problem was that AIA management was under pressure as well. The airline’s contract with the Department of Defense was lucrative, but it was also demanding, and the DoD would penalize AIA if too many flights were late leaving Norfolk. In an effort to keep its contracts, AIA pushed its pilots to the limit, frequently exploiting legal loopholes like the one that allowed the crew of flight 808 to complete the trip to Guantanamo Bay. Furthermore, AIA executives tried to hire as few management-level staff as possible, forcing many to work jobs that should have been split between three or more people. As a result, compliance with regulations fell by the wayside as personnel struggled simply to complete the day-to-day tasks needed to keep the airline running. At one point, the FAA inspector became so frustrated with AIA’s inability to update its flight operations manuals that he threatened to delay approval of the airline’s Boeing 747 operations until it brought the manuals up to code. All of these factors were symptomatic of an airline that valued expansion and profit at the expense of its human employees.

At the conclusion of its investigation, the NTSB made the unprecedented decision to list pilot fatigue not merely as a contributing factor, but as the probable cause of the accident. It was plain to the investigators that the crew was completely competent under normal circumstances, and that the accident would not have occurred if fatigue had not impaired their judgment. In its final report, the NTSB recommended that the FAA close the loophole allowing airlines to exempt ferry flights from duty time limits; that the FAA update its duty time regulations to take into account the latest research regarding fatigue; that AIA provide better crew resource management training, and training about aircraft performance at steep bank angles; that the Department of Defense brief all civilian contract pilots about procedures and hazards at designated special airports; and that the FAA require airlines to teach pilots about the effects of fatigue.

After the accident, Chapo, Curran, and Richmond were forced to live with the consequences of their failure. Curran lost a leg in the crash, but he was able to continue flying for a time, and he later became an investigator for the NTSB. Unfortunately, Chapo suffered back injuries that forced him to retire from flying. But Richmond managed to make a full recovery and returned to his career, eventually working his way up to the rank of captain.

Today, duty time limits for pilots in the United States are much stricter, and no pilot would ever be on duty for as long as the crew of AIA flight 808. Nevertheless, fatigue is a constant problem faced by any pilot flying night shifts, and every crewmember must remain cognizant of their level of tiredness at all times. Fatigue continues to play a role in crashes and near misses around the world, and the best thing a pilot can do to prevent a similar accident is to know his or her own limitations.

“You know, I think about those things a lot, and I would want people to realize that it can happen to them. If you’re fatigued, call it in.” — Captain James Chapo

Source- https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/