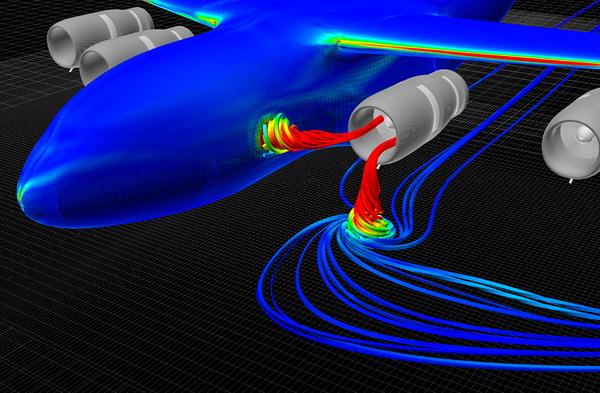

The votices are formed at the inlet of a jet engine or the fan. This happens because, as the engine sucks in the air, a region of low pressure is created in front of the fan.

If there is water vapour present in the atmosphere or in the region of low pressure, they condenses to form tiny droplets of water. Now, as the engine sucks in air, the condensed water vapours flow into the engine like the picture shown below

The flow of the condensed water vapour shows the flow of air inside the engine. If there is no moisture or water vapour present there, this vortices cannot be seen.

Vortices can be produced and ingested into the intake of a turbofan and turbojet aero engine during high power operation near solid surfaces. This can happen either on the runway during take‐off or during engine test runs in a test cell.

The vortex can throw debris into the intake or cause the compressor to stall causing significant damage to the engine and may require major overhaul. The ability to predict the onset of a vortex is therefore extremely valuable to the industry and could potentially save millions of dollars in overhaul costs.

The factors that determines whether or not a vortex forms include engine thrust level, geometric factors such as the distance between the engine core and the ground and the size of the engine core, and flow conditions such as ambient vorticity and height of boundary layer. Computational fluid dynamic studies have been carried out by the authors to attempt to predict the effects that these factors have on the threshold of vortex formation.

These works include the first reported studies of numerical predictions of the vortex formation threshold on both the runway or test cell scenarios and include factors that have not been previously studied either numerically or experimentally.