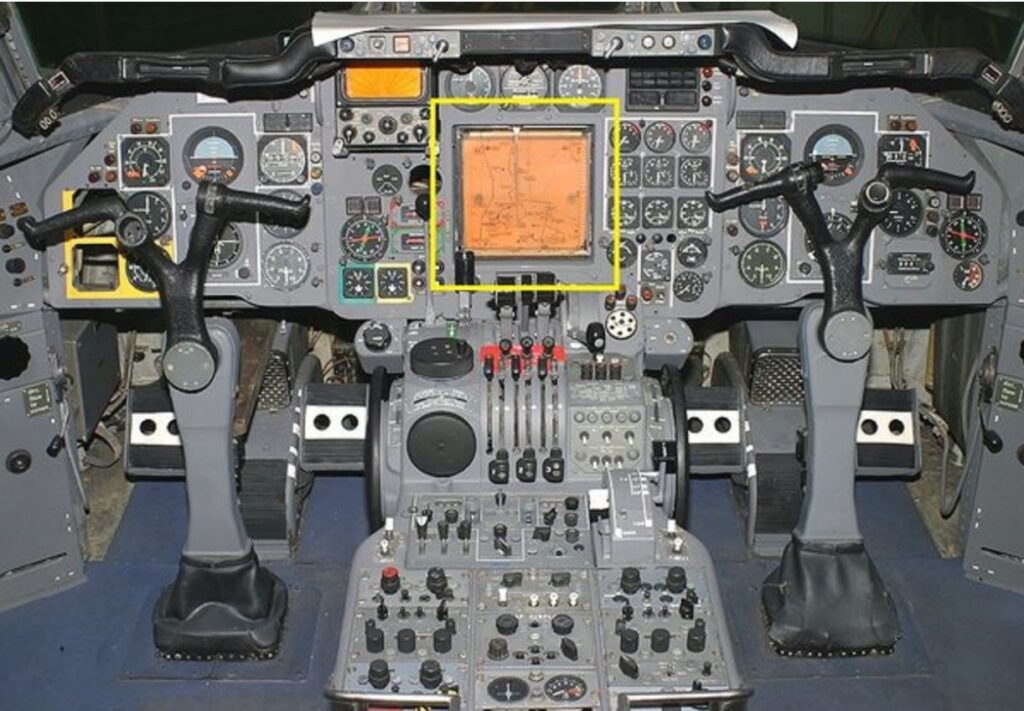

The British were the first to come up with an analogue ‘GPS’ system for aircraft. The HS-121 Trident (which by the way was the first aircraft to even perform an automatic landing in the late 60s) had an actual moving map in the cockpit that showed the pilots the live position of the aircraft. It was a world beater given that the aircraft was built in the early 60s. Forget the GPS, even the Inertial navigation systems were in their early development stages back then, and were not widely used by aircraft.

The map display of the Trident.

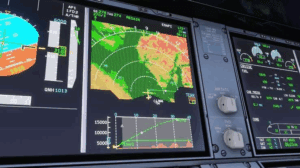

How it worked was through a simple doppler radar. The radar sent out four beams, two from the front of the aircraft and two from the back of the aircraft. As the aircraft moves, the beams experience a frequency shift due to doppler effect. When the aircraft radar emitted beams hit the ground, it reflects back at the aircraft at a different frequency if the aircraft was moving across the ground. This shift in frequency is proportional to ground speed. The reason why we need four beams is because the aircraft climbs and descends. If only one beam is emitted, the ground speed cannot be accurately calculated. For instance in a climb, there will be difference in frequency between the front beams and the beams at the back. In a climb the front beam will move up. So, this can be added to the back beams to cancel out any deviations.

When the aircraft drifts due to wind, again there is a difference in the frequency between the left and right beams. For example, if the aircraft drifts to the right of the actual flight path due to a wind from the left, there will be a frequency shift between the left and the right beams. This frequency shift is used to calculate the drift angle and the ground speed is updated using it.

The doppler radar is designed to project out four separate beams directed towards the surface.

Now, let us really see how this information is translated into the map. With the radar we can get an accurate ground speed. If we know the speed and also if we know the time, we can very simply calculate the distance. To figure out where we are, with this information we will just need the aircraft heading data which can come from the heading indication of the aircraft. The pilots during the pre-flight inserts a simple paper chart into the map display, then they use the map control panel to position the stylus or the pen of the display to the correct location (starting point) of the flight. As the aircraft moves, the calculated position data is fed into the system, and the stylus draws the path on the map. The coolest part of this navigation system is that, it does not require any signals from a ground based navigational aid. It was all self contained. God save the Queen.

The stylus which is used to draw the path on the map.

Author – Anas Maaz – Airline pilot. Airbus A320/A321